When you see an exciting idea do you ever look beneath the surface to find the story behind it? If we were able to examine the actual process that gave birth to the idea, we would find layer upon layer of small stories. These little anecdotes are the foundation of the idea. Stories not only play a fundamental role in shaping ideas, they give the work cultural value. I will begin by sharing the story behind Floatyard, a proposal for floating housing in Charlestown, Massachusetts. I hope these little anecdotes will shift your interpretation of Floatyard from “paper architecture” to a meaningful idea.

Whose idea was floating housing? While floating by Charlestown Navy Yard and Pier 5 on a harbor cruise, Ed Nardi, President of Cresset Development, overheard a remark that sounded something like this: “whoever develops that pier better have deep pockets”. The comment prompted Ed to find a better way. He discovered a cost efficient alternative to rebuilding the pier by simply removing it and replacing it with a floating complex.

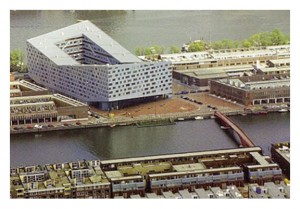

Campbell, what’s up with the bug analogy? Floatyard’s form is not inspired by insects. Robert Campbell describes Floatyard as a “cubist bug” in his Boston Globe article. But how could he know? He never asked the team. The form is inspired by a multi-family housing complex in the Amsterdam Oostelijke.

I pulled out one of my travel photos to serve as the project precedent. The managing principal on the project, Brian Healy and I had seen the building in Amsterdam several years ago and while Brian was enamored by the hidden courtyard I was drawn to the lift of the form.

After successfully re-working the form onto the Charlestown site, we realized we had intuitively selected the most appropriate configuration. Stacking units along the edge provided privacy and unobstructed views to the harbor for all residents. Boston Harbor is a cold, damp, windy environment much of the year. During the months of November through March temperatures and relative humidity make harbor side zones unbearable. The courtyard, which serves as the main circulation zone, acts as a micro-climate to protect residents from the brutal elements. And by lifting the eastern, front-facing facade, we were able to preserve an essential view corridor from the courtyard out to the harbor.

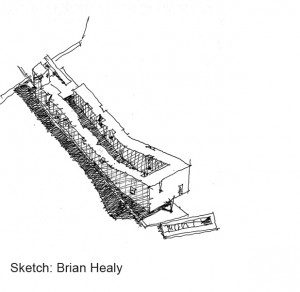

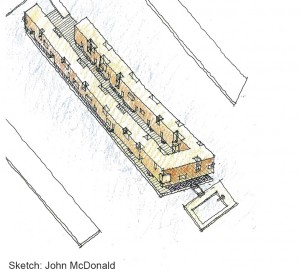

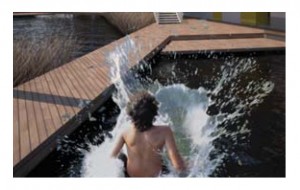

What happened to the pool? Architect John McDonald produced an initial series of sketches to convey the vision. It is was the language John developed in this sketch that we carried through to the final concept. Unfortunately, John had to move on mid-project and when we lost him, we also lost this adorable little floating pool. John McDonald was the former Design Director at Perkins + Will, he is now an architect with Elkus Manfredi.

It’s 2 am and we are still studying fenestration. John Nelson, an intern from Tulane was a huge force in the early stage of development. John worked with me to further develop the facades and we explored fenestration patterning into the early morning hours.

Are we keeping the hydraulics? Matt Pierce is the man behind the base structure. These muscular support members morphed out of many earlier iterations that range from thin and angular to curvaceous hydraulic-like form. We were often asked: “can the building bounce up and down?” The answer is no!

Who says you can’t swim in Boston harbor? Jiseok Park did. When I suggested we provide access for swimmers– he exclaimed “you cant swim in the harbor, its not clean.” I said “why not?” And we designed a floating wetland system to help keep the courtyard water clean.

What the hell is that? Imagine looking down to your feet and through the floor over water, boats, swimmers and perhaps harbor wildlife. With this window you can! Matt and I call this the Barnacle. I also envisioned reworking this form into a second iteration that could serve as some sort of small, overhead watercraft launch!

Quincy vs. East Boston. Fabricating and assembling Floatyard at a shipyard will make construction far more cost efficient. Using water as the primary transportation method eliminates the size limitations of ground transport. And because channels in the inner harbor are able to accommodate massive vessels such as the 700 foot petroleum tanker, it is possible to transport large sections of Floatyard and it might even be possible to transport the entire building all at once. The question then becomes where to assemble. Will it be the spacious well equipped Fore River shipyard, 10 miles away? Or the smaller, unequipped East Boston waterfront, less than 1 mile.

The lights are blinking, it sounds like I am in a freight train, the streets are flooding, but I must get this proposal finished! I wrote the Floatyard narrative and compiled the proposal — a 32 page, full spread document – exactly one year ago during Hurricane Sandy. The programming was developed through rigorous brainstorming sessions with my teammates, all of whom are mentioned in this story. That brutal storm made the project even more meaningful to me. Floating homes and/or floating buildings could reduce the economical impact made by storms such as Hurricane Sandy. These structures can rise with the storm surge unlike land based structures. I hope to see one here in Boston Harbor during the next big hurricane.

Floatyard received a 2013 Progressive Architecture Award, it was shortlisted in the World Architecture Festival and it continues to receive international recognition.

To read more about Floatyard visit:

http://www.architectmagazine.com/multifamily/award-floatyard.aspx

http://blog.shiftboston.org/2013/03/floatyard-housing-for-hurricane-prone-areas